Loading...

9th July 2016

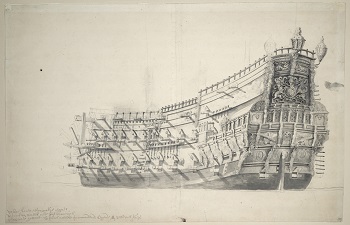

Constant Reformation was the name of a warship in the English Civil War, so-called perhaps as a reminder that reformation is a process, not an event. The European Union has been resisting this process for some time but the UK’s decision to leave looks certain to start a reformation.

Brexit brings with it heightened uncertainty and the risk of policy error. That said, Brexit has come about because of a litany of previous policy errors. We are cautiously optimistic this decision will lead to much-needed policy reform and therefore prove to be beneficial for both the global economy and long-term investment returns. However, we believe investors must now adapt their strategies to preserve wealth and survive in the new environment.

The scientist and philosopher Thomas Kuhn studied paradigm shifts in scientific theories, periods when one world view is replaced with another. One of his greatest insights came in recognising how paradigm shifts are usually led by laymen and resisted by the incumbent experts who have a vested interest in preserving the status quo.

When new thinking is needed, Kuhn showed the experts are usually intransigent, dogmatic and unwilling to objectively criticise their own ideas. It therefore falls to outsiders to rock the boat and push new ideas forward. As the paradigm shift progresses, the incumbent experts become increasingly resentful of their loss of status as new experts emerge to replace them.

Having closely watched the UK’s referendum campaign on European Union membership and the subsequent response of the commentariat – the body of expert journalists, economists, financiers and politicians – I am increasingly of the view that the real story of Brexit is not about the UK at all and perhaps not even about the European Union. Rather it is about the rejection of incumbent expert opinion. When, prior to the referendum, the leading leave campaigner Michael Gove MP said “people in this country have had enough of experts” he was widely derided, yet a few days later the British electorate proved him correct by ignoring the overwhelming body of expert advice.

The reaction of the experts to the Brexit decision has been fascinating. Commentators have recast democracy as populism or, in the case of The Economist magazine, as anarchy: the cover of last week’s issue carried the headline ‘Anarchy in the UK’ above a flagpole flying a pair of Union Jack underpants. The website ForeignPolicy.com carries an article with the remarkable title ‘It’s Time for the Elites to Rise Up Against the Ignorant Masses’. Writing in The Times newspaper, the Institute for Fiscal Studies’ director Paul Johnson offers an analysis of why economists’ warnings against Brexit were ignored – “We economists must face the plain truth that the referendum showed our failings.” – in which he takes “as given that we economists were collectively right about the economic consequences of leaving the EU,” before concluding that they “have failed to communicate basic economic concepts to politicians, journalists and businesspeople, never mind the public”.

Immediately the decision of the British voters became known, the commentariat settled on an angry narrative of misinformation by the leave camp (though actually there was plenty of misinformation on all sides) and democracy was derided as populism; the wisdom of crowds, an idea usually trumpeted by economists, was never mentioned. The experts have written their own report card, awarding themselves a D- for presentation but an A+ for content. Willingness to contemplate the idea that the voters made the right choice has been almost completely absent.

The expert consensus has so far resisted acknowledging that the remain campaign may have failed not through misinformation and miscommunication but rather because the EU’s policies and especially its core project, the Euro zone, are demonstrably failing. The electorate simply recognised this reality and opted for what they perceived to be the lower risk option of Brexit, despite the experts’ contrary warnings.

The European Union simply did not offer the remain campaigners the material they needed to win the argument. They could not direct the voters’ attentions toward the EU’s economic successes for fear they might notice its failings: the low growth; the rising inequality between the prosperous north and the impoverished south; the eye-wateringly high youth unemployment; the capital controls; and the brutal austerity imposed upon Greece. Without viable positive arguments, they were forced into a negative campaign resting on a series of promised punishments: job losses, tax rises, interest rate rises and the threat that the European Union would impose punitive trade barriers on the UK as a deterrent to prevent other countries from also trying to leave. Arguably playing up the ‘vengeful EU scenario’ was the most ill-advised of all strategies: who would want to remain in a club where members must be retained under duress? It is also telling that the only significant intervention by a foreign statesman came when President Obama promised another punishment, in his case threatening to send Britain to the back of the queue for American trade negotiations if voters made the wrong choice. On the other side, senior European statesmen presenting a positive case to remain within the union were conspicuous by their absence.

In short, the European Union is not performing as promised by the experts. The voters in the UK and quite likely in other member countries are ahead of the experts in recognising this reality. This fact is causing experts to lose sway over the voters. The experts are lashing out at the consequences of Brexit rather than seeking to understand the underlying causes of Brexit and then, crucially, to remedy those causes. This schism between voters and experts is strikingly similar to the conditions which Thomas Kuhn identified as prevailing prior to scientific paradigm shifts. (Arguably the same process is playing out in America where the non-expert Trump is gaining popularity relative to establishment experts – but that can wait for another letter.) If this reading of the Brexit event is correct, we may be witnessing the birth pains of a new world order, a new geopolitical and macroeconomic paradigm.

This begs the questions: what has gone wrong? What has to change?

Much of the Brexit campaign was fought over the issues known as the four freedoms of the single European market. These are the freedom of movement of capital, goods, services and labour. The remain camp were adamant these four freedoms must be preserved while the leave camp were just as adamant that the fourth freedom in particular – the freedom of movement of labour – should be curtailed.

The logic behind the four freedoms comes directly from the mindset of neoclassical economics and its blinkered adherence to the mantra of market efficiency. The rationale of the four freedoms is that by maximising competition and minimising controls the private sector of the whole European economy will reach an optimal stable equilibrium: capital and labour must be allowed to move to where it is most productive, and the goods and services produced by capital and labour must be allowed to be sold where it is most profitable.

The four freedoms, as with so much of economics, ignores destabilising self-reinforcing processes which operate within the private sector and push the economic system away from a state of optimal equilibrium. Since these destabilising forces are not recognised by neoclassical economic theory, the requirement for countervailing stabilising forces, provided by the government sector, also goes unrecognised. The problem arises because the European Union has created perfect freedom of movement for the wealth-creating side of the economy, the private sector, while simultaneously imposing perfect rigidity on the redistributing side of the the economy, the state sector, by constraining taxation, spending and government borrowing and preventing cross-border fiscal transfers.

It is easy to see how the asymmetric approach to the private and state sectors leads to wealth polarisation within Europe. More successful regions will offer higher wages, generate higher tax revenues and therefore be able to impose a lower tax burden upon their companies and workers. This will lead to a virtuous cycle whereby successful countries attract the most productive companies and workers. By contrast less successful regions will suffer lower tax receipts, as a result of net emigration, requiring the imposition of a higher tax burden upon those who remain. Greece is currently suffering just this destructive, self-reinforcing spiral of fiscal austerity begetting more fiscal austerity.

The four freedoms of the single market, coupled with the fiscal straitjacket and monetary rigidity of the Euro zone, therefore produce powerful wealth polarising forces – prosperity begets prosperity in regions like Germany while austerity begets austerity in regions like Greece. Counteracting these polarising forces requires the introduction of a balancing mechanism in the form of fiscal transfers from the rich to the poorer regions, a system that is quite normal within most single currency zones – namely countries – but is forbidden within the Euro zone.

Put bluntly, the cross-border migration of people from poor to rich countries, which so energised the leave campaign, is almost certainly being amplified by a deficit of cross-border fiscal redistribution from rich to poor countries, which also energised the leave campaign.

In its current form the European Union, and especially the Euro zone, has either too many or too few freedoms. Either the mobility of the private sector – people, capital, goods and services – must become more geographically constrained, or the mobility of the state sector – tax revenue, government spending and government borrowing – must be less geographically constrained. In other words, the European Union project needs to be either completed, by effectively turning the region into a single country with a single fiscal system, or it needs to be unwound and returned to a looser association of genuinely sovereign states, with independent fiscal policies and currencies.

Europe, and especially the Euro zone, needs either to integrate or disintegrate; continuing with the current arrangement will in all likelihood ghettoise entire countries and thus serve to incubate social unrest and political extremism.

Our cautious optimism on the Brexit decision rests on the expectation that expert opinion will now be forced to recognise the shortcomings of the European Union’s architecture, thereby forcing the required reforms. These reforms may involve further integration or disintegration, quite possibly with different parts of the union choosing different paths. Handled correctly, either of these paths could and should be preferable to the status quo.

That said, we do not expect this process to be smooth. The experts have been instructed to implement a reform they believe to be unnecessary for reasons they do not understand by an electorate they do not respect. Political turbulence and therefore market turbulence are likely to be elevated for years to come.

Investment implications

If the paradigm is changing, as we believe, then the main impact for investors may ultimately be seen through the longer term outlook for inflation. In our view, the defining error of the existing paradigm has been to pursue policies designed to relentlessly drive debt levels ever higher. It appears likely that the the new policy paradigm will have to find a mechanism to repudiate much of this accumulated debt through default, debt cancellation or inflation. For this reason, we expect that real assets – equities and real estate – will provide much safer vehicles to preserve and grow value in coming years, than will nominal assets such as cash and bonds.

On a personal note, my hometown of Sunderland has now become famous for delivering an especially decisive vote to leave the EU. In a previous period of paradigm change, the aforementioned English Civil War, Sunderland also chose to back the reformers rather than the defenders of the status quo by supporting Oliver Cromwell’s parliamentarians. Sunderland-born John Lilburne, otherwise known as Freeborn John, was one of the founders of the Levellers’ movement and a close friend of Cromwell, whose statue now stands outside of the British parliament. Sunderland has a tradition of being on the right side of history in periods of revolution: today’s experts may be well advised to take note.

George Cooper is Chief Investment Officer at Equitile Investment Ltd