Loading...

20th January 2020

The new decade is getting off to a good start for equity investors. Stock markets around the world are making new all-time highs and, with Google now worth more than a trillion dollars, there are now four trillion-dollar companies in the world: Apple, Microsoft, Google and Saudi Aramco. If we ignore Petro China, which briefly reached a trillion-dollar valuation on its flotation back in 2007, before immediately falling by 70%, Apple was the first to become a “genuine” trillion-dollar company back in 2018.

The new decade is getting off to a good start for equity investors. Stock markets around the world are making new all-time highs and, with Google now worth more than a trillion dollars, there are now four trillion-dollar companies in the world: Apple, Microsoft, Google and Saudi Aramco. If we ignore Petro China, which briefly reached a trillion-dollar valuation on its flotation back in 2007, before immediately falling by 70%, Apple was the first to become a “genuine” trillion-dollar company back in 2018.

The history of companies with record breaking market capitalisations is an interesting one, with some useful lessons for investors.

The first billion-dollar company was United States Steel, formed in 1901 when J.P. Morgan merged Carnegie Steel with his own Federal Steel, American Steel and an assortment of smaller companies, under the chairmanship of Charles Schwab. The merger created the largest company in the world, with a market capitalisation of $1.4 billion. Prior to the Wall Street crash, shares in United States Steel reached a peak $261.75, trading under the simple stock market ticker ‘X’ which, 119 years later, the company still uses. Today the ‘X’ ticker of United States Steel carries a price of just over $10 and the company a market capitalisation of just $1.8 billion. To be fair, today’s United States Steel is not the sole descendent of J.P. Morgan’s original entity, so those figures are not like-for-like comparisons. Nevertheless, it is fair to say the last 119 years have not been kind to investors in United States Steel.

General Motors was also a product of the boom years of the early 1900’s. Founded in 1908 as a holding company to purchase Buick Motor Company it quickly went on to acquire a stable of iconic American automobile brands: Oldsmobile, Cadillac, Oakland (Pontiac) and Chevrolet to mention some. By 1955, General Motors had become the world’s biggest private sector employer and the first company worth ten billion-dollars. But this period marked the peak of GM’s success. Through the 1960s, 70s and 80s quality problems saw GM lose profitability and market share to foreign competition. Despite having somewhat addressed these issues by the 1990s, GM remained in a financially fragile position going into the Global Financial Crisis of 2007 and, on June 1st 2009, was forced to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. The company was restructured into a new entity in July 2009 and re-floated in November 2010 in a $20 billion Initial Public Offering, then the biggest IPO in U.S. history.

Today GM is worth about $50 billion, but this value is held by the new shareholders, the original shareholders having been largely wiped out by the Chapter 11 process. In the ten years since GM’s rebirth, its stock price is unchanged. History has not been kind to GM’s shareholders either.

The 100 billion dollar milestone was reached in 1995 by General Electric, another company with a long and storied history, also created by the venerable J.P.Morgan.

In 1889 J.P.Morgan, who had financed Thomas Edison’s early research into electricity, merged his Drexel Morgan and Co with Edison’s companies forming Edison General Electric Company which by 1896 had become simply General Electric when it entered the Dow Jones Industrial Average Index as one of the twelve founding members.

General Electric has been one of the most dynamic and innovative companies in history pioneering: electricity distribution, power generation, the development of radio, television and many of the labour-saving home appliances we take for granted today.

More recently, under the leadership of Jack Welsh, from 1981 to 2001, GE built a major financial services division, arguably becoming a bank in all but name. This was, at least initially, a hugely successful strategy as, under Welsh’s leadership, GE reached a peak valuation of $594 billion in 2000. At that time, GE looked like a strong contender to become the world’s first trillion-dollar company.

The story since Jack Welsh’s departure has been less auspicious. GE’s share price has fallen by almost 80% from its peak in 2000, arguably due to the legacy of excessive leverage and financial creativity, which originally drove its share price higher in the 1990s. Today GE’s market capitalisation is barely above $100-billion and some commentators openly question the long-term viability of the company. In June 2018 after 122 years GE became the last of the founding members of the Dow Jones Industrial Average to be removed from the index.

Today it is easy to focus on how these corporate superstars fell from grace, but focussing on this negative aspect of the story misses the much more important underlying positive story.

After its early success the products of United States Steel became commoditised and as a result its margins were competed away. This was bad for its shareholders, but it was good for the economy as a whole and it was especially good for the customers of United States Steel. Lower steel prices were one of the factors allowing General Motors, and others, to bring car ownership to the masses and allowing General Electric to put appliances in so many homes. General Motors, General Electric and a host of other manufacturers were able to boost the living standards for millions of people on the back of cheaper steel prices. Far more value was created, both for society and for shareholders, from lower steel prices than was lost in the margin collapse of United States Steel alone.

Having first driven down margins in the steel industry, market forces moved up the food chain driving down margins for other manufactured goods, including GM’s cars and GE’s appliances. GE managed to buck the trend for a few decades by stepping into financial services but, in recent decades, margins in that industry have also contracted.

The story of these stock market superstars is a repeating one. High margins from innovative new technologies lead to stratospheric share prices, but those margins are eventually competed away. Good investments become bad investments. But lowering the price of old technologies makes new technologies viable. The success of today’s stock market superstars, Apple, Microsoft and Google, would be impossible without the without the infrastructure enabled by shrinking margins in companies like United States Steel and General Electric.

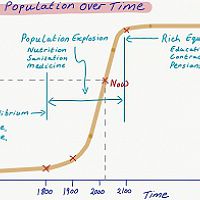

It took 54 years to get from a one-billion-dollar company to a 10-billion-dollar company. It took only 40 more years to go up another tenfold to the first 100-billion-dollar company. Then just another 23 years later the first trillion-dollar company valuation was reached. These tenfold increases in stock market values keep happening and happen at an accelerating pace. This is good news for investors and good news for society. If the trend continues, and we firmly believe it will, the first 10-trillion-dollar company may occur early in the next decade.

It is counterintuitive, but nevertheless true, that the demise of yesterday’s superstar companies is a necessary process to enable tomorrow’s superstar companies to emerge. This creative destruction, as Joseph Schumpeter called it, is a vital part of a healthy dynamic economy and is responsible for driving up the living standards for so many people around the world.

We believe the global economy is currently in the early stages of a new phase of the industrial revolution. Arguably the first phase of the industrial revolution was based on steam technology and the external-combustion engine, while the second phase was based on electrical technology and the internal combustion engine. Both phases improved productivity largely by automating human labour. The current phase, we believe, can usefully be thought of as automating human decision making. Data collection, storage, processing, calculation, transmission and ultimately artificial intelligence are all part of this new phase and all rely on the advanced electronic and software technologies of, for example, Apple, Microsoft and Google.

Today, the Equitile Resilience Fund is invested in Apple, Microsoft and Google and we are optimistic about the prospects for all three of these trillion-dollar companies. We would not rule out any one of them becoming the first 10 trillion-dollar company. But we are even more optimistic about the ongoing process of innovation within the economy. So, although we expect them all to thrive in the foreseeable future we are also expecting, at some point, their margins to be competed away.

Apple may become tomorrow’s Sony (Walkman’s were once as cool as iPhones), Microsoft could become tomorrow’s Lotus Software (Lotus once dominated the spreadsheet market) and Google could become tomorrow’s Netscape (people googled with Netscape before googling became a word). Although we hope one of our trillion-dollar companies will become the first 10 trillion-dollar company, we know history suggests this is a longshot. It is more likely that we will have to adapt your portfolio to capture the next record breaker.

The story of stock market leadership moving from United States Steel to General Motors to General Electric and now to Apple, is a positive one. In nominal dollars Apple is worth almost exactly one thousand times as much as United States Steel when it became the world’s biggest company. But it is also a story that warns against a buy-and-hold investment philosophy. History shows even the best companies eventually become some of the worst investments.

Adopting a buy-and-hold investment strategy is often held out as a discipline to strive for. It is seen as virtuous because it minimises transaction costs. But the minimisation of transaction costs must be set against costs of sticking with yesterday’s companies. In an innovative economy, taken to extreme, a buy-and-hold investment strategy is a path to almost certain failure. Buy and hold is fragile in the face of innovation.

In our view, the “do nothing buy-and-hold strategy” is both pessimistic and arrogant: pessimistic in suggesting competition will not drive down existing margins and successful new companies will not emerge; arrogant in suggesting we can know today which companies will be the winners far into the future.

We don’t believe we can reliably see economic developments years into the future and we also believe, many of tomorrow’s superstar companies are yet to be born or if they have been born may be beavering away in obscurity.

In short, the story of yesterday’s stock market champions says be optimistic but also be prepared to adapt in order to survive and thrive.

Investment Letter - Constant Reformation

2

Investment Letter - Constant Reformation

2

A New Maestro? Observations on an important speech by Fed Chairman Powell

2

A New Maestro? Observations on an important speech by Fed Chairman Powell

2

Is corporate debt addictive?

2

Is corporate debt addictive?

2

Captain Kirk and the science of economics

2

Captain Kirk and the science of economics

2

Brochure

1

Brochure

1

Meerkats and Market Behaviour - Thoughts on October's stock market fall

2

Meerkats and Market Behaviour - Thoughts on October's stock market fall

2

Can fair fees make active managers more sustainable?

2

Can fair fees make active managers more sustainable?

2

Monetary Policy on a War Footing

2

Monetary Policy on a War Footing

2

Facts not Opinions

2

Facts not Opinions

2

Revolutionary Fervour

2

Revolutionary Fervour

2

Depressed lobsters and the dividend yield trap

2

Depressed lobsters and the dividend yield trap

2

Hanging the Wrong Contract?

2

Hanging the Wrong Contract?

2

Invest in Resilience

1

Invest in Resilience

1

2016: A Tale of Two Walls

2

2016: A Tale of Two Walls

2

Over Easy - Can Monetary Policy Become Self-Defeating?

2

Over Easy - Can Monetary Policy Become Self-Defeating?

2

The Lost Shield? - The small print in Trump's tax plan

2

The Lost Shield? - The small print in Trump's tax plan

2

Revival of the Fittest

2

Revival of the Fittest

2

In Search of Stability & Growth - If only Europe was more like the US

2

In Search of Stability & Growth - If only Europe was more like the US

2

An Impossible Trinity?

2

An Impossible Trinity?

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part I

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part I

2

Modern Monetary Theory - The Magic Money Tree

2

Modern Monetary Theory - The Magic Money Tree

2

Why ownership matters more than ever

2

Why ownership matters more than ever

2

Build a company on prudence and trust, not debt

2

Build a company on prudence and trust, not debt

2

The Anxiety Machine - The end of the world isn't nigh

2

The Anxiety Machine - The end of the world isn't nigh

2

The unspoken political truth about debt

2

The unspoken political truth about debt

2

Still Flashing Green: Equities in a world of higher growth and financial repression

2

Still Flashing Green: Equities in a world of higher growth and financial repression

2

Tales of an Astronaut - Lessons from the Unknown

2

Tales of an Astronaut - Lessons from the Unknown

2

Regulating Psychopaths

2

Regulating Psychopaths

2

Crisis Economics

2

Crisis Economics

2

Investment Letter - Eternal Adaptation

2

Investment Letter - Eternal Adaptation

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part II

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part II

2

Norway Moves to America - Mean reversion and industrial revolutions

2

Register for Updates

12345678

-2

Norway Moves to America - Mean reversion and industrial revolutions

2

Register for Updates

12345678

-2