Credit in the Twenty First Century

I have been asked to re-post four articles origionally written in April/May 2014 about the ideas of Thomas Piketty in his book Capital in the Twenty First Century: The Magical Mathematics of Mr Piketty Part 1 and Part 2, Credit in the Twenty First Century and The Horrible History of Mr Piketty

Credit in the Twenty First Century

The economist Thomas Piketty has a new theory of capitalism and he is using it to argue for a radical overhaul of the global tax system – he wants an annual wealth tax, imposed on all our assets, including our houses, at a top rate of 2 percent per year. So far, he has convinced a lot of leading economists and he is doing his best to persuade policymakers also. The Nobel prize-winner Paul Krugman says: ‘if you think you’ve found an obvious hole, empirical or logical, in Piketty, you’re very probably wrong.’ – I suspect there is such a hole and it’s a big one.

Make no mistake, the ideas in Mr Piketty’s new book Capital in the Twenty-First Century are important. If his new theory of capitalism is correct we risk a future of Dickensian income inequality – it would be disastrous to ignore him. On the other hand, if his theory is incorrect his tax policies could crush economic growth – it would be disastrous to follow him. Either way, it is worth understanding his ideas and probing for their weaknesses.

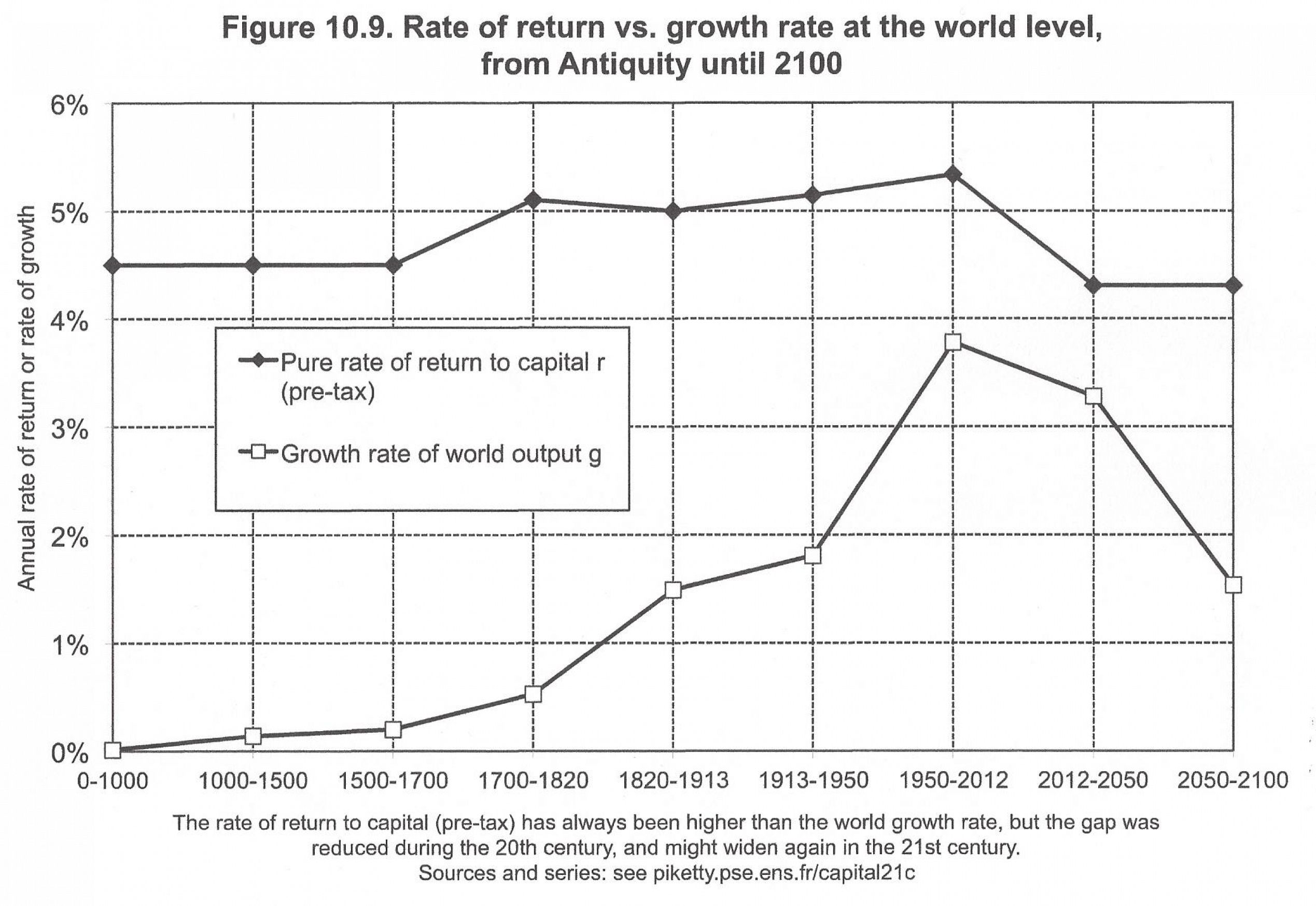

Piketty’s new theory all turns on a simple inequality, his now famous, r > g. This means the return on capital, r, is always greater than the growth rate of the economy, g. To understand why this is so important we have to delve into the theory and data in Piketty’s book.

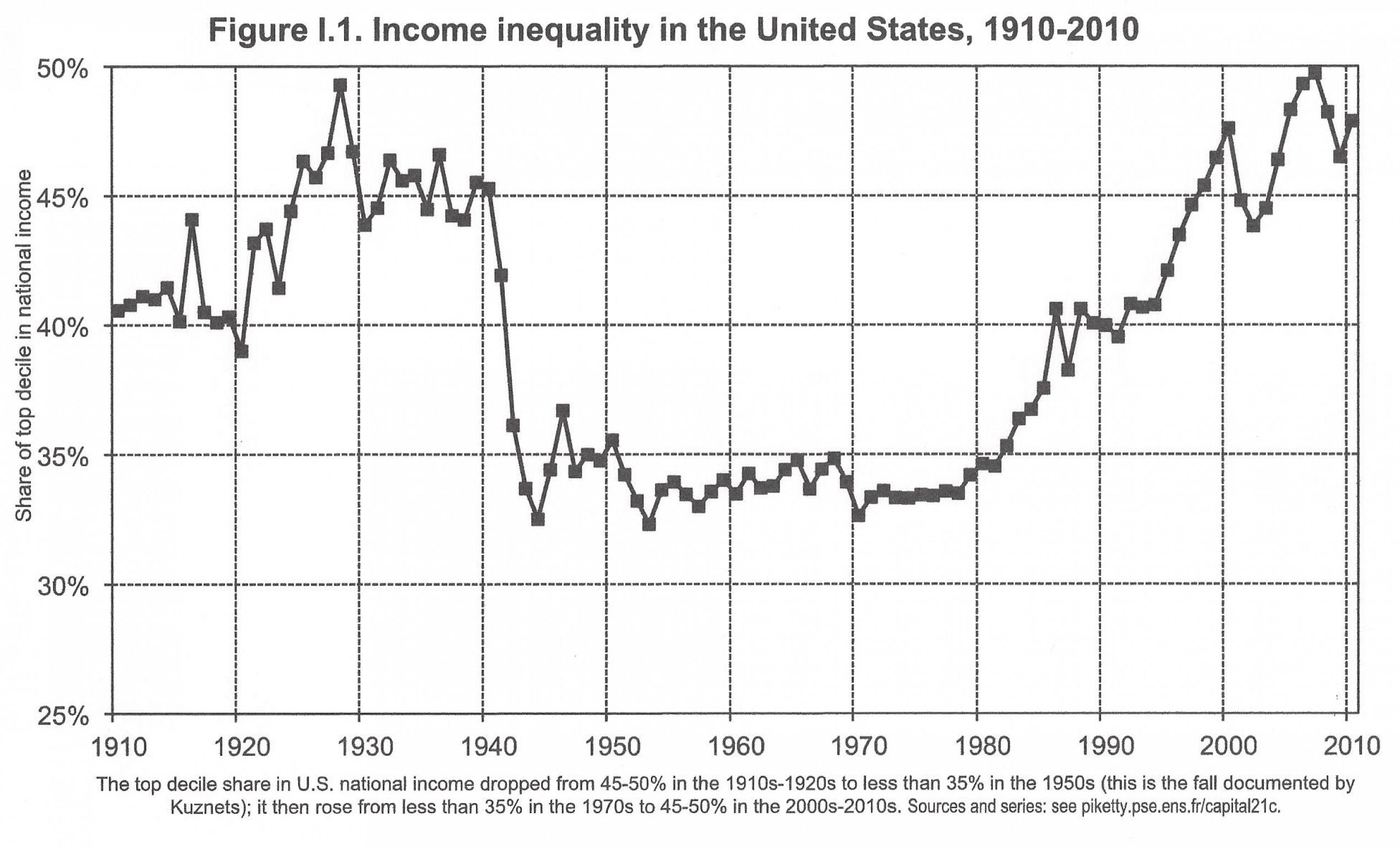

Piketty is known for his studies of income inequality. His most famous chart shows, since the 1980’s, the top 10% of wage earners in the United States have been taking home a steadily larger and larger slice of the economic pie. Currently they are taking almost half of all earnings, a figure not seen since prior to World War II (Fig I.1 p24).

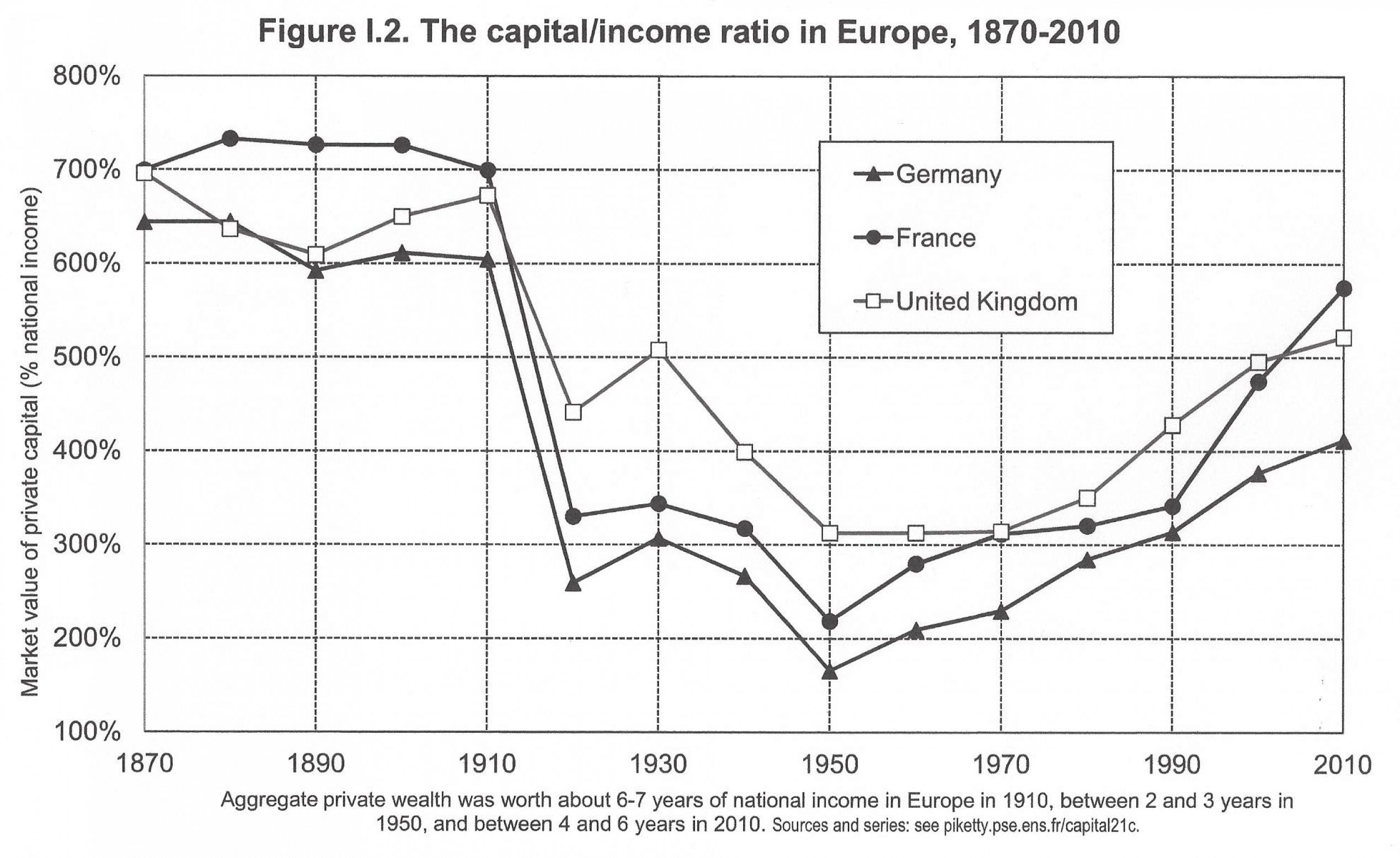

Income inequality is only a small part of Piketty’s new book. He now has a new concern – wealth inequality. To Piketty, wealth inequality is an even bigger problem than income inequality because wealth is less evenly spread and is growing much faster than wages, a trend he expects to continue. (Fig I.2, P26).

To understand why Piketty is so worried about the consequences of wealth inequality it is necessary to understand his new theory of capitalism. Fortunately it’s very simple.

Piketty explains that the equilibrium ratio of national assets to national income, β, is determined by the economy’s annual savings rate, s, and its annual growth rate, g, according to the formula:β =s/g . So, if an economy saves 10% of its income and grows at 2% it will eventually accumulate assets worth five years of annual income, β = 10%/2% = 5.

Piketty also notes that the share of the national income going to the owners of the economy’s capital is simply the value of the capital, β, multiplied by the average return on capital, r. Therefore, if an economy has 5 years of capital, yielding 5%, the owners of that capital will enjoy 5x5% or 25% of the annual income of the economy, leaving the other 75% for the workers.

Piketty expects that economic growth will decline, due to lower birth rates and less technological progress. Anticipating lower demographic growth is uncontroversial, forecasting falling productivity growth is a bit more speculative. To illustrate his argument, I will consider what happens as economic growth declines from 2% to just 1%.

According to Piketty’s model this prospective halving of economic growth will cause a doubling of the value of the capital of the economy. Assuming the savings rate stays constant, at say 10%, the capital stock will go from being worth 5 to 10 years of income.

So far there is nothing new or controversial in Piketty’s ideas.

The novelty in Piketty’s thinking is that, he believes, the return on capital, r, is something akin to a universal economic constant. Piketty thinks capital always earns an average real yield of 4-5%, which is itself always higher than the economic growth rate, which rarely gets above 2%, hence r > g. For simplicity I will assume a return on capital of 5%.

We can now see the source of Piketty’s concern. As growth falls from 2% to 1% the value of the capital in the economy will rise from being worth 5 to 10 years of annual income. As that capital earns a fixed 5% yield, the returns enjoyed by the owners of the capital will increase from 25% to 50% of the annual income. Consequently the share of income available for wages will fall from 75% to 50% percent.

Put bluntly, as growth halves, the rich owners of capital can expect their earnings to double while the workers can expect their wages to be cut by one third. This is why Piketty anticipates a Dickensian level of inequality in a future low-growth economy.

This logic leads directly to Piketty’s call for a 2% annual tax on the value of capital. By imposing this tax, as growth falls and capital values rise, the revenue from the 2% wealth tax will automatically rise, providing greater revenues to subsidise the falling wages of the workers.

Before leaping Krugman-like onto Piketty’s bandwagon we should pause for thought.

Until just a few weeks ago conventional wisdom said that we should expect the returns on capital to move up and down with economic growth – high growth means high yields and low growth means low yields. Indeed, the working assumption of many in the financial markets was that the average real return on the whole stock of capital was equal to the real rate of economic growth: r = g , rather than Piketty’s r > g.

The distinction between r > g and r = g is important. If the return on capital moves up and down with economic growth then, as growth halves, the value of capital will double. But this doubling of capital will be exactly offset by a halving of its yield, leaving the returns on capital unchanged. In other words, if r = g, changing rates of economic growth will do nothing to shift the relative balance between the incomes of workers and the owners of capital. Piketty is admirably forthright on the importance of his r > g assertion: ‘This fundamental inequality, which I will write as r > g … sums up the overall logic of my conclusions.’ P25

This brings me to a curious aspect of Piketty’s 600+ page book which is generously peppered with charts and tables. Over the last three or four decades we have had a series of excellent empirical tests of Piketty’s inequality. Economic growth in Japan slumped dramatically at the end of the 1980’s, followed more recently by similar slumps in Europe and North America. Over this period the keeping of records of both growth and yields has been comprehensive – yet we find none of this, very relevant, data in Piketty’s book.

Unfortunately for Piketty’s thesis, we have found, reliably and repeatedly, that when economic growth falls asset yields also move down – often dramatically. The data of recent decades overwhelmingly refutes Piketty’s claim that the return on capital is independent of and substantially higher than the underlying economic growth rate. The data is far more supportive of the conventional wisdom, r = g and not of Piketty’s new claim r > g. The perilous funding position of many pension funds and the recent decision to remove the requirement for pensioners to buy annuities are both direct consequence of investors being unable to invest at the returns Piketty claims are available.

Piketty provides some very curious data to support his r > g claim, the most interesting of which is a chart showing economic growth rates and returns on capital from the birth of Christ to almost 100 years from now. So far this part of Piketty’s data has attracted little attention, but it is by far the most important data in his book.

(Fig 10.9, P354).

As discussed, the brief period for which we do have reliable data refutes Piketty’s r > g inequality and we can say nothing with certainty about the future. Therefore the empirical support for Piketty’s thesis rests, oddly, on his estimates of economic growth and capital returns in antiquity.

We can be surprisingly precise in our estimates of economic growth in antiquity – there wasn't any, or at least very little. We know this because archaeological evidence tells us that population growth rates were very limited and technological progress almost absent in this time. Living standards in the year 1,000 were not markedly better than those when Christ was alive. For this to be the case the average annual economic growth in the first millennium must have been very close to zero, as Piketty’s data suggests.

On the face of it, it is more difficult to say anything reliable about the returns on capital in this time, but with a little imagination we may be able to learn something interesting.

Consider an isolated island kingdom in the year zero. It is a perfect feudal society where the King owns everything and his subjects work for him. Half of the island is covered in productive farmland, the other half of the land is too rocky to farm. The King employs all of the workers in the economy. Most workers are employed to farm the productive land, while a few are employed to clear rocks from the unproductive land. Over many generations the kingdom is handed down from father to son. Each new King continues investing in the expansion of the island’s productive land. By the year 1,000 the whole of the island’s land has been converted into productive farmland.

Over the millennium, the island’s economy would have doubled in real terms, as the farmland expanded – a cumulative growth of 100%. The King in the year 1,000 would own an economy twice as large as that of his ancestor the first King. The cumulative return on the first King’s original capital would have been 100% in line with the 100% growth of the economy. This requires that real economic growth and real capital returns must be identical, r = g.

This helps explain a potential problem with Piketty’s logic. If the total stock of capital represents ownership of the entire economy: how can the entire capital stock grow at a rate that differs, in any way, from the growth of the whole economy? Indeed, it could be argued, that the whole capital stock and the whole economy are one in the same thing. If this logic proves valid – and it should be tested – conventional wisdom is correct: average real returns on capital and average real economic growth rates are synonymous. If so, then perhaps we can add a third fundamental law of capitalism to Piketty’s collection: r ≡ g. In which case there are very big empirical and logical holes Piketty’s theory.

If r = g is found to be valid, how can we explain the gap between r and g shown in Piketty’s chart in ancient times? It may be that these yields represent not a return on capital but rather a return on credit. Let me explain:

During the millennium-long island dynasty, it would be quite possible for the islanders to borrow and lend between themselves, perhaps at quite high interest rates. The interest rates, on these loans, would represent only the charges on the debts and credits between citizens. Since every credit was exactly offset by its matching debit these transactions would, by construction, net to exactly zero and would not therefore represent any ownership of the island’s capital. However, the interest rates charged on these loans would represent a mechanism for transferring income between citizens. If the interest rates charged were sufficiently high and the stock of credit sufficiently large this could represent a powerful wealth polarizing force acting between the citizens of the island. The King may own all of the capital of the island but still, through the mechanism of credit, the wealth of individual citizens could become quite polarized relative to one another. I do not know for certain, but I suspect, the interest rates recorded in antiquity, and shown in Piketty’s chart, are more representative of returns on credit rather than the average real returns available on whole stock of the economy’s capital in those times.

Piketty has done the world a service in placing income inequality at the centre of the economic debate, where it should be. He has also got people thinking about whether or not capitalism suffers a tendency toward wealth polarization – it must do, otherwise progressive taxation would have long since depleted the fortunes of the rich. But the validity of his new theory is doubtful. If his r > g relationship proves incorrect and real yields on capital do in fact move with underlying economic growth then, in a low growth environment, the imposition of a 2% wealth tax could push real yields on capital negative potentially bringing entrepreneurial activity to a shuddering halt. What’s more we should consider the pro-cyclical nature of such a taxation: in a recession when profits collapse the owners of capital could be forced to sell assets, into a falling market, in order to fund taxes levied on historic elevated valuations. For this reason alone taxation based on tangible income received rather than based on ephemeral market valuations is to be preferred.

Progressives may wish to consider another aspect of Piketty’s argument. Piketty’s thesis says inequality is caused by slowing growth. Therefore, Piketty’s story says that even if inequality is addressed growth will not return – demographic factors are fixed and innovation he sees as exogenous. This offers little in the way of incentives for the tough political decisions necessary to achieve reform. There are other, more persuasive, more optimistic, arguments that put the causality the other way round – excessive inequality causes slow growth. These arguments offer more powerful incentives for constructive reform.

Conclusion

I suspect Piketty’s thesis r > g will not prove robust to either empirical or theoretical scrutiny. His proposed wealth tax looks to be neither desirable, necessary nor attainable. His focus on capital rather than credit as the principal wealth polarizing mechanism is, I believe, a misdirection which risks diverting attention away from credit, banking, financial market and monetary reform. For these reasons I worry that Piketty’s thesis may ultimately prove to be something of a Trojan horse for genuine reformers.