Growth won’t die of old age

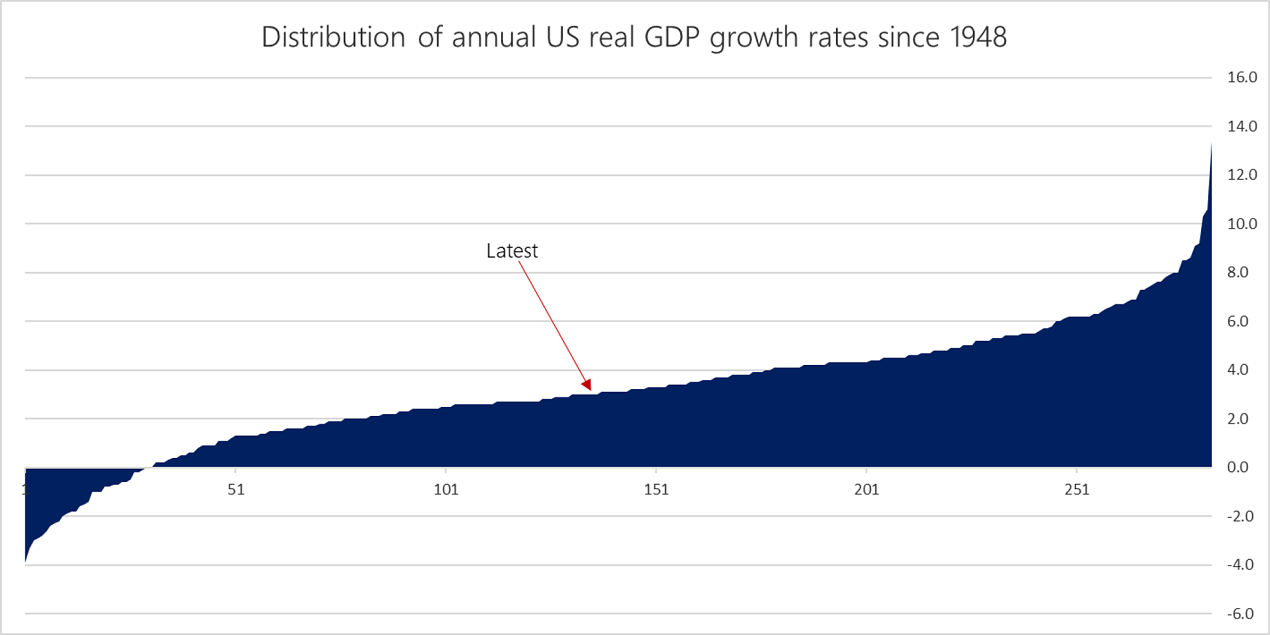

Our recent posting, Beware the Mean Reversionists, showed how the current US growth spurt is unremarkable in terms of its longevity or impact and, even if it was an outlier, the current growth rate itself is average by historic standards. Of all 283 twelve-month rolling growth rates since 1948, the current run-rate is about midway.

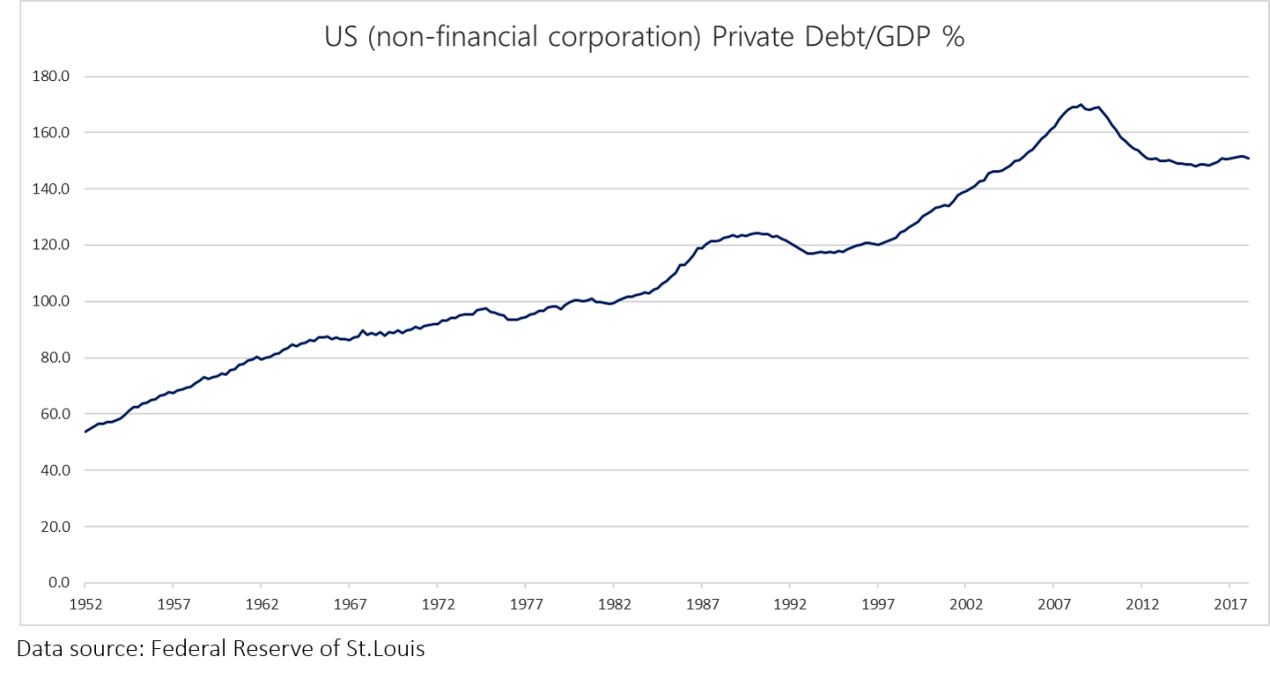

When economies do slow dramatically it’s often down to debt. When households and companies overstretch themselves, they effectively experience an economic exhaustion. Growth slows when the private sector comes to realise it’s overspent and over-indebted.

When we look at the headline numbers in this respect, we are reassured. The US private sector is not as indebted relative to GDP as it was before the Global Financial Crisis.

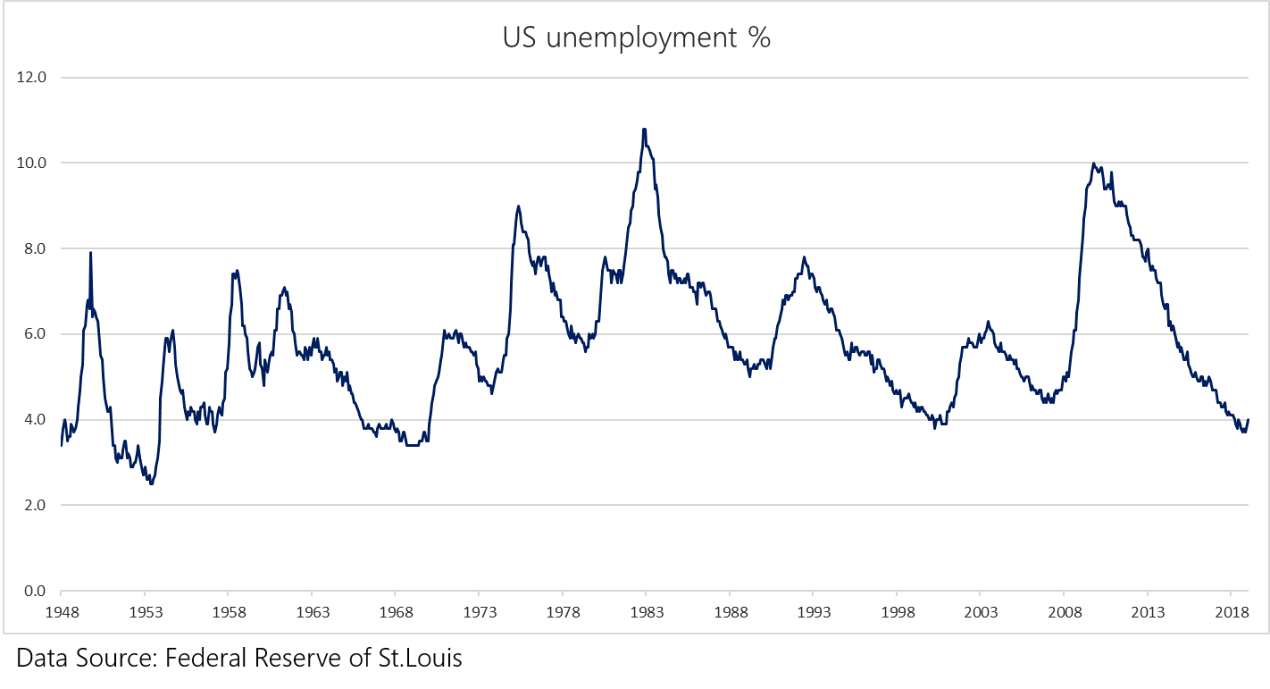

Moreover, although some pundits have pointed to historically low unemployment as a limit to growth, there’s room for optimism.

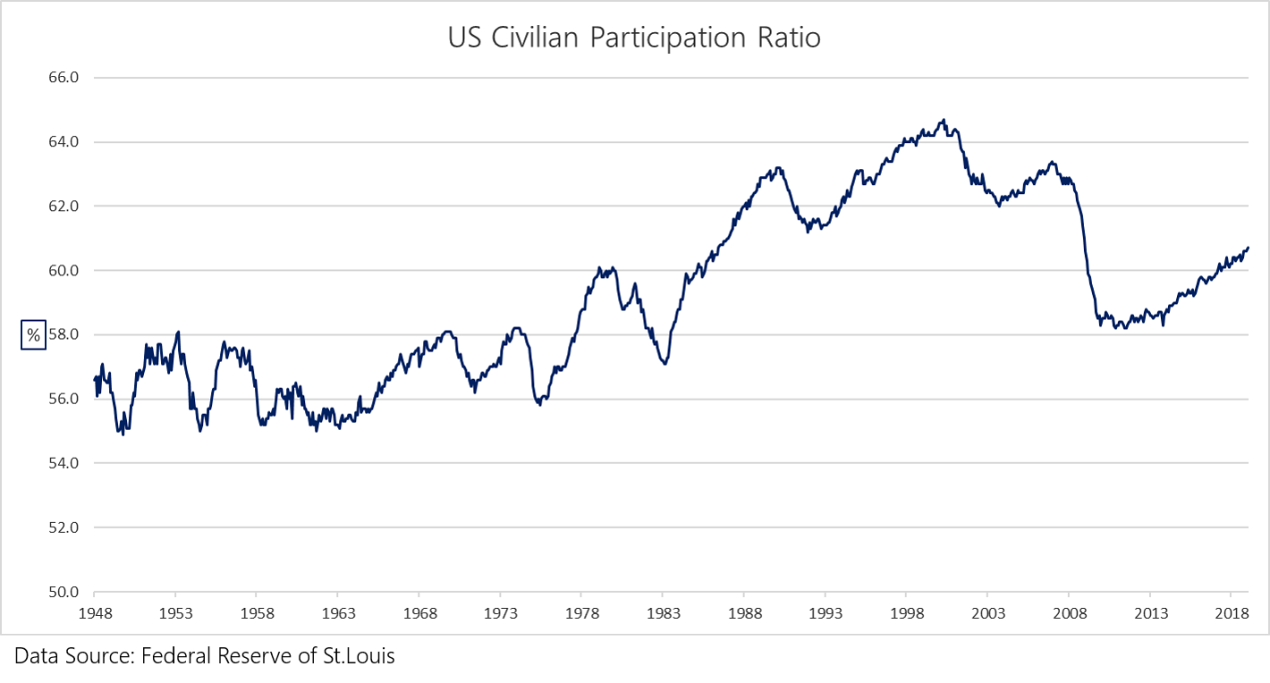

The recession after the financial crisis, for a myriad of reasons, kicked a high number of participants out of the jobs market – a fall too steep to be driven by demographics alone. It’s not unreasonable, therefore, to assume that the participation rate - the percentage of the civilian population that make themselves available for work - could pick up meaningfully from here.

The global economic backdrop isn’t providing a tail-wind for the US right now, but headline data in the US at least doesn’t suggest the current growth spurt will die of old age.