The Horrible History of Mr Piketty

I have been asked to re-post four articles origionally written in April/May 2014 about the ideas of Thomas Piketty in his book Capital in the Twenty First Century: The Magical Mathematics of Mr Piketty Part 1 and Part 2, Credit in the Twenty First Century and The Horrible History of Mr Piketty

The Horrible History of Mr Piketty

This weekend’s Eurovision Song contest saw Austria romp to victory with 290 points, leaving France languishing in last place with only 2 points. Naturally this got me thinking about how the economic ideas of these two great nations stack up against one another. More specifically how Thomas Piketty’s theory of capital accumulation compares with Joseph Schumpeter’s creative-destruction of capital.

***

Whenever it comes to a clash of ideas between the Austrian and orthodox schools of economics you can be sure that methodological differences will figure somewhere in the discussion, so let’s get that out of the way first.

The world is too complicated to understand in the raw so we use simplifying models make sense of what we see. Invariably our simplifying models don’t describe the world perfectly, leaving us with an annoying gap between reality and model – the error term. If the gap is small enough we ignore it, if it is large we are forced to construct secondary models to explain it. Put differently, we construct primary models to explain how the world works and secondary models to rationalize why the primary models don’t work – the former provide the explanations and the latter the excuses.

If we have a good understanding of the system, the primary models will do the heavy lifting leaving little need for the supporting excuses. If we have a poor understanding of the system the gap between model and reality will be large and we will find ourselves defending our models with all sorts of complex excuses.

The orthodox and Austrian schools of economics have developed two very different approaches to modelling economic systems. Orthodox economics insists that the primary model be framed in mathematical language, just like the grownup sciences. These mathematical models tend to describe the economy, with a few equations, as something akin to a mechanistic clockwork system. However, when it comes to providing the secondary excuses, explaining why real economies deviate from the mathematics, orthodox economics is forced to fall back on looser narrative models. By contrast the Austrian school argues that the narrative models usually dominate the clockwork mathematics. So the Austrians prefer to cut out the middle man and go directly to the narrative approach. Put differently, Austrians prefer to be roughly right rather than precisely wrong.

I have sympathy with the honesty and pragmatism of the Austrian school. On the other hand the orthodox school’s approach at least makes it explicit where the model ends and the excuses begin: the former is the maths and the latter the story. The downside of this mixed approach is the necessity to consider the integrity of the mathematical model and the plausibility of its supporting narrative.

The description of capitalism presented in Thomas Piketty’s new book is a good example of the mixed mathematical/narrative genre. The primary model is presented via three mathematical relationships: r > g; β=s/g; α= β×r. These describe a mechanistic process of capital accumulation and the division of national income between workers and the owners of capital. The secondary model is a narrative of capital destruction, centered on World War I:

“In both Britain and France, the total value of national capital fluctuated between six and seven years of national income throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, up to 1914. Then, after World War I, the capital/income ratio suddenly plummeted, and it continued to fall during the Depression and World War II…

The capital/income ratio fell by nearly two-thirds between 1914 and 1945 and then more than doubled in the period 1945-2012…

Broadly speaking it was the wars of the twentieth century that wiped away the past to create the illusion that capitalism had been structurally transformed.” p117/118

So far, most of the focus of attention has been on Piketty’s mathematical model with little attention given to his supporting narrative.

In the following I am going to play devil’s advocate, providing an alternative story of both the process of European capital destruction and its recent rebound. This alternate story has a distinctly Austrian tone, emphasizing first Schumpeter’s creative-destruction of capital and later the use of monetary policy to manipulate asset prices.

Before I start I should emphasize, this alternative narrative agrees with Piketty’s core message: inequality is problematically high. However, it leads to a different explanation for this problem and therefor points toward different remedial policies.

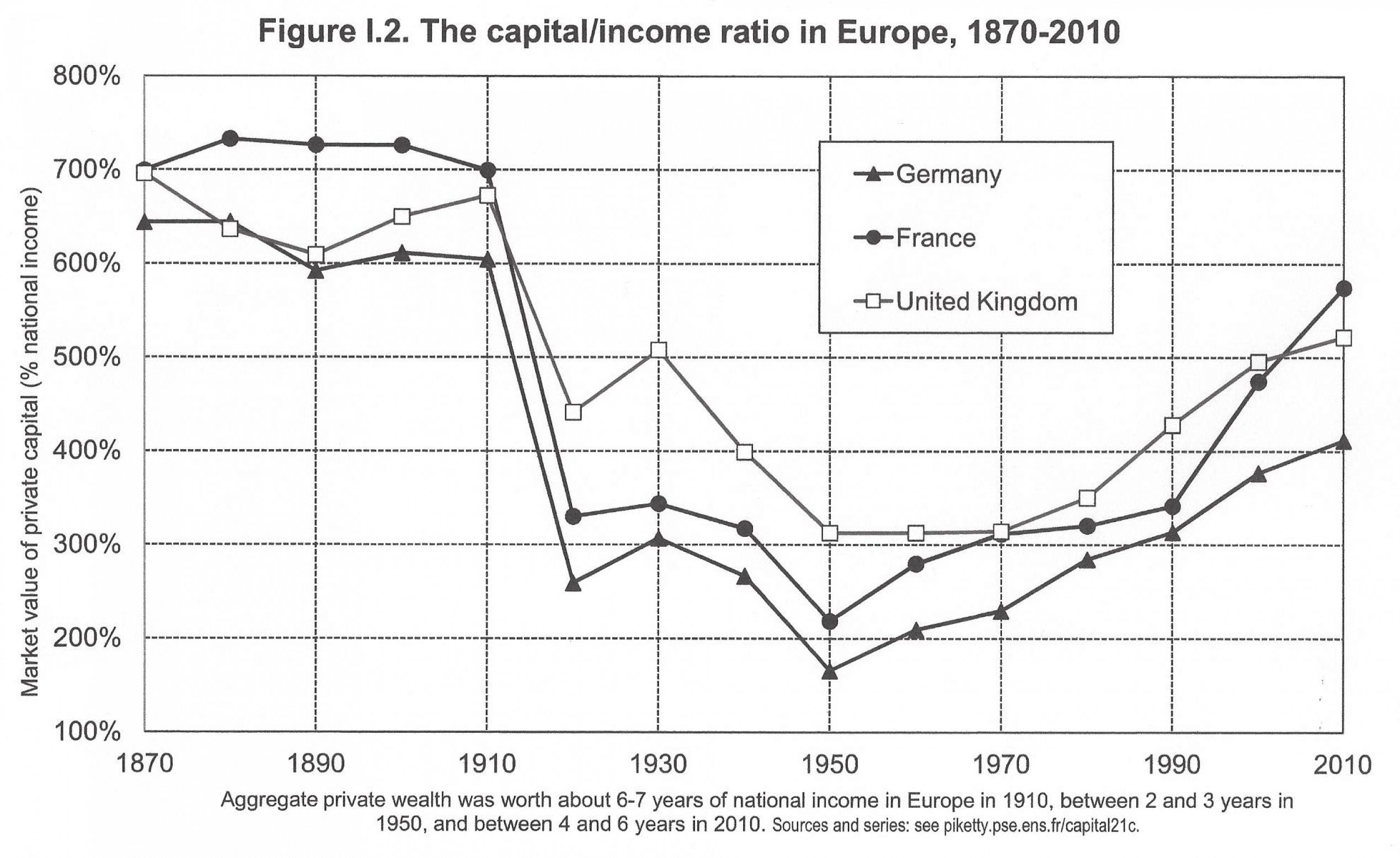

Piketty presents the following chart to show the precipitous decline in the value of European capital due to World War I. (Figure I.2.)

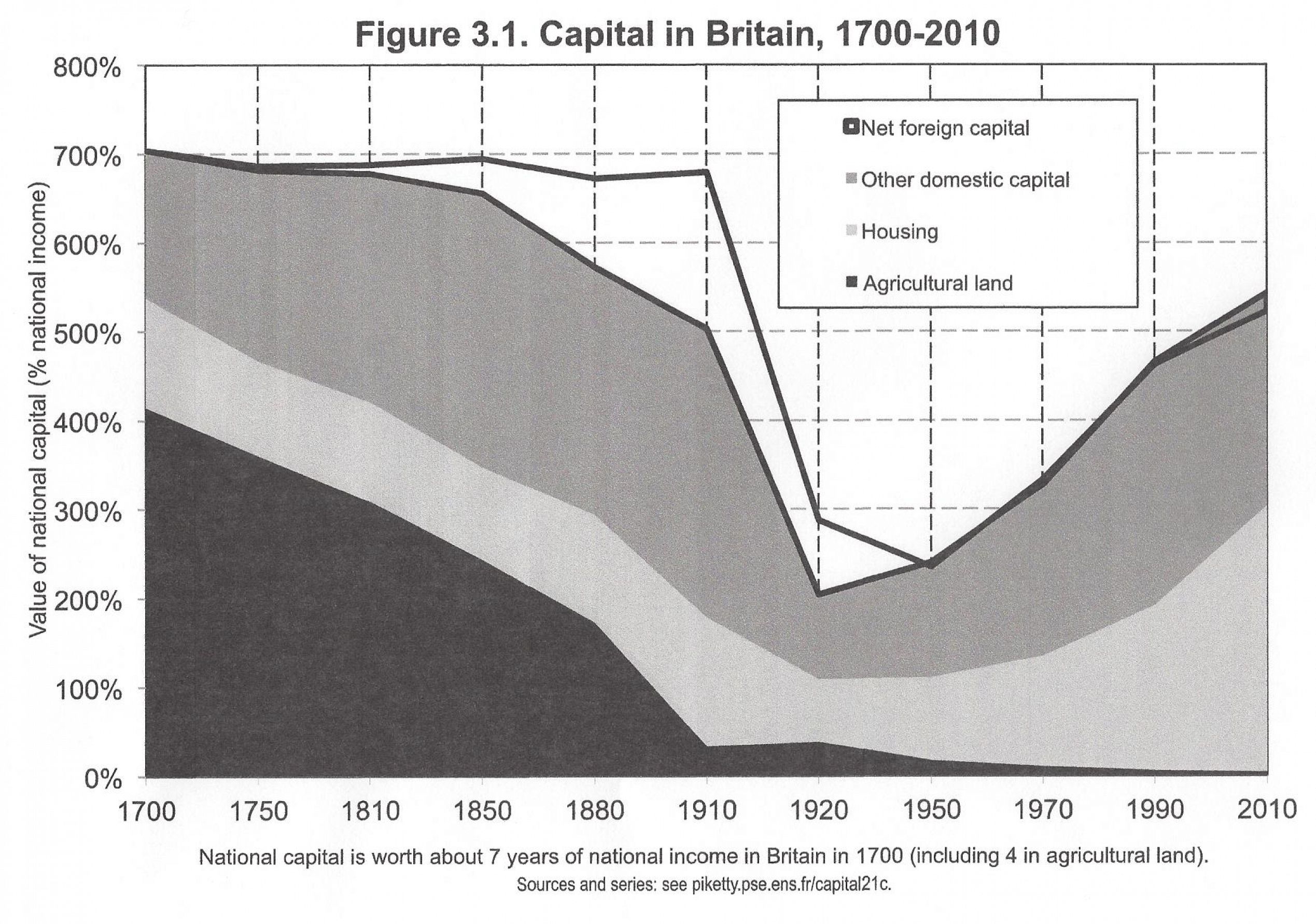

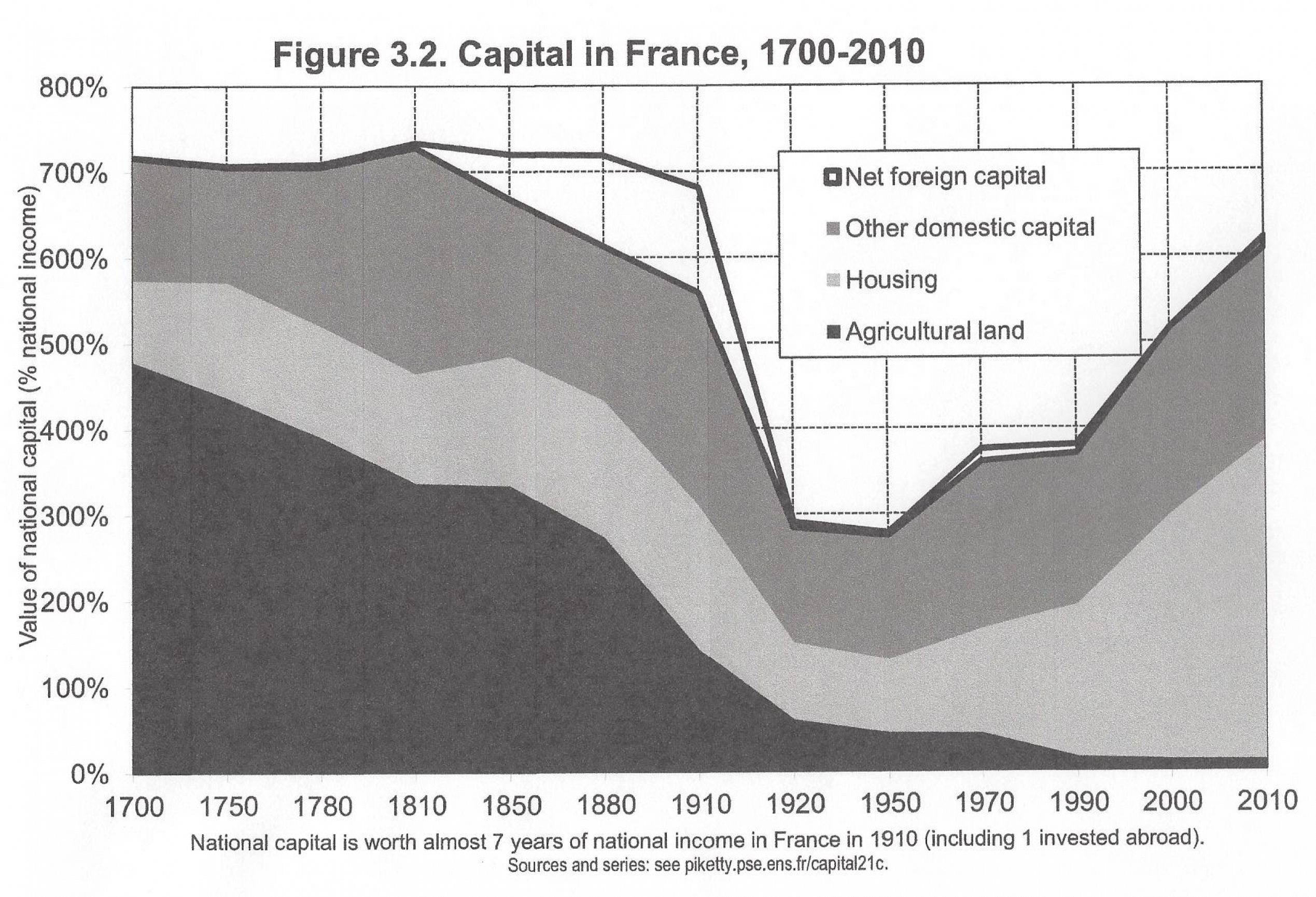

Later in the book Piketty provides a richer data set showing the composition of the different components of capital which make up the data in Figure I.2. These are figures 3.1, 3.2 and 4.1 showing the value of agricultural land, housing, other domestic capital and net foreign capital for Britain, France and Germany respectively.

The charts of the composition of capital in Britain and France are especially informative. These show that the movements in the value of capital, from 1700 to the present day, have been dominated by two processes. The first was the near total destruction of the value of European agricultural land, the dominant form of capital in 1700. The second is the more recent rise in the value of housing over the last three or four decades.

If we choose to focus on the changes in the value of Agricultural land and Housing, individually, it becomes more difficult to associate their changing values with the two World Wars. The decline of agricultural land values began in Europe long before WWI while the surge in the value of housing really only took-off at the start of the 1980’s.

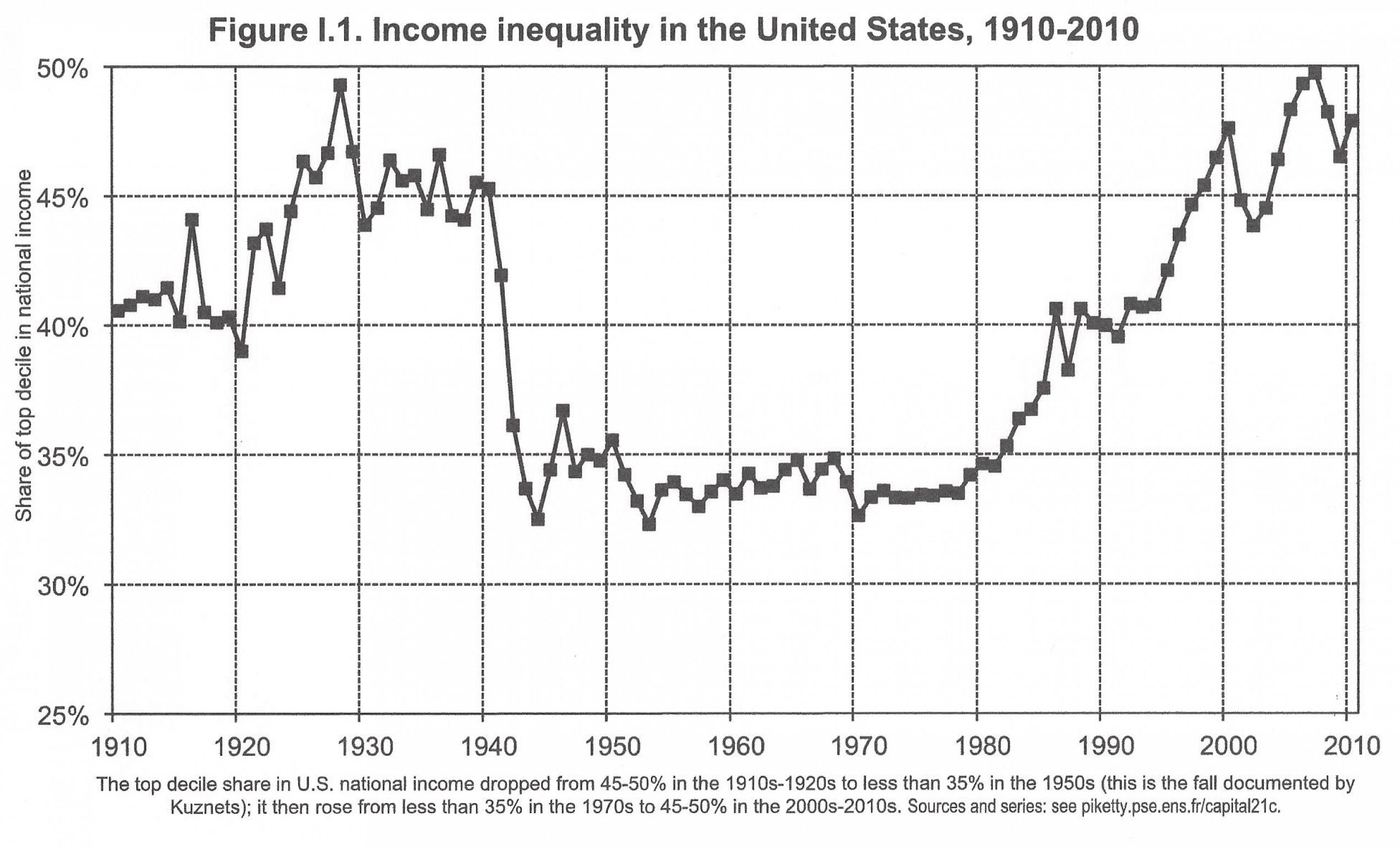

It is worth also looking at Piketty’s first chart, Figure I.1, showing the share of total income going to the top 10% of wage earners in America.

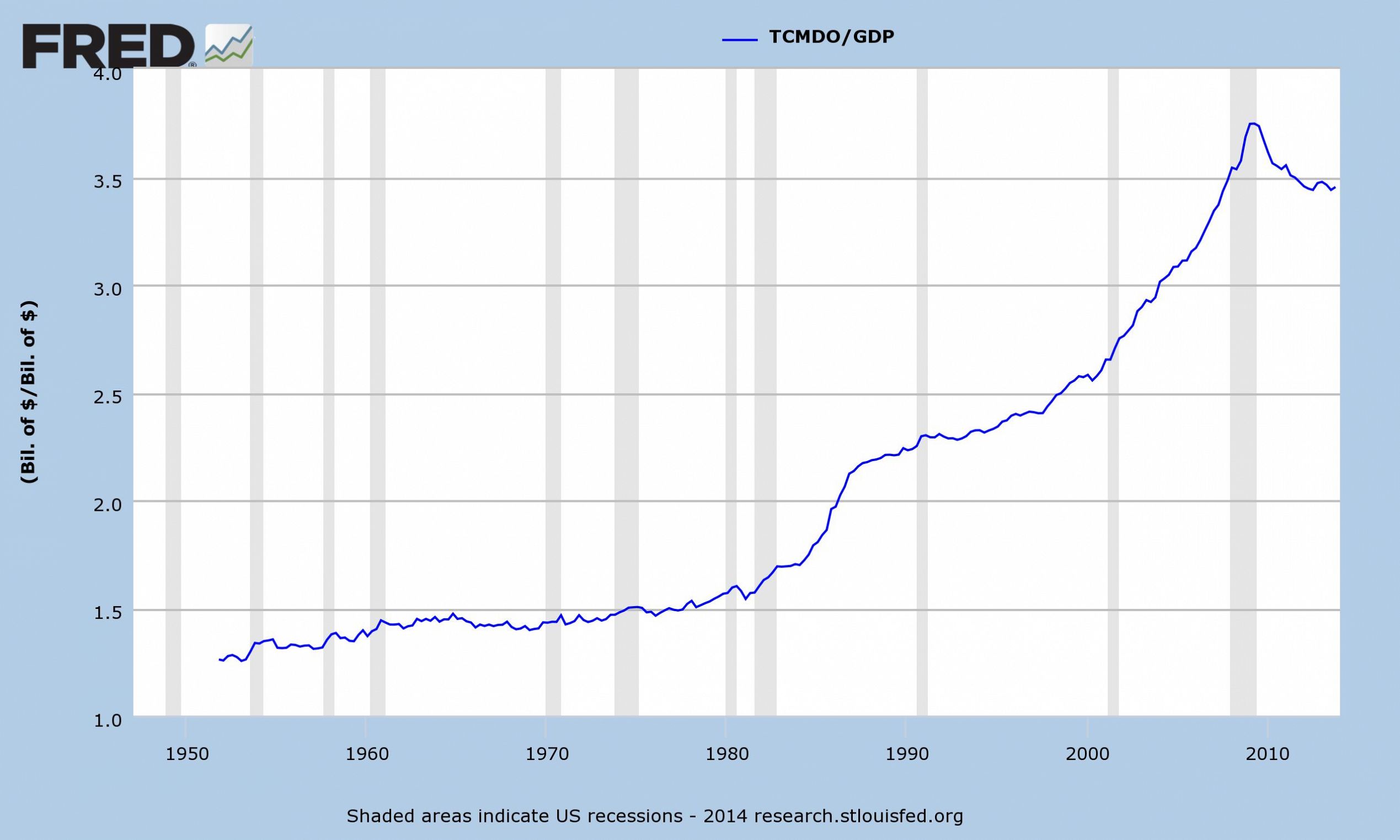

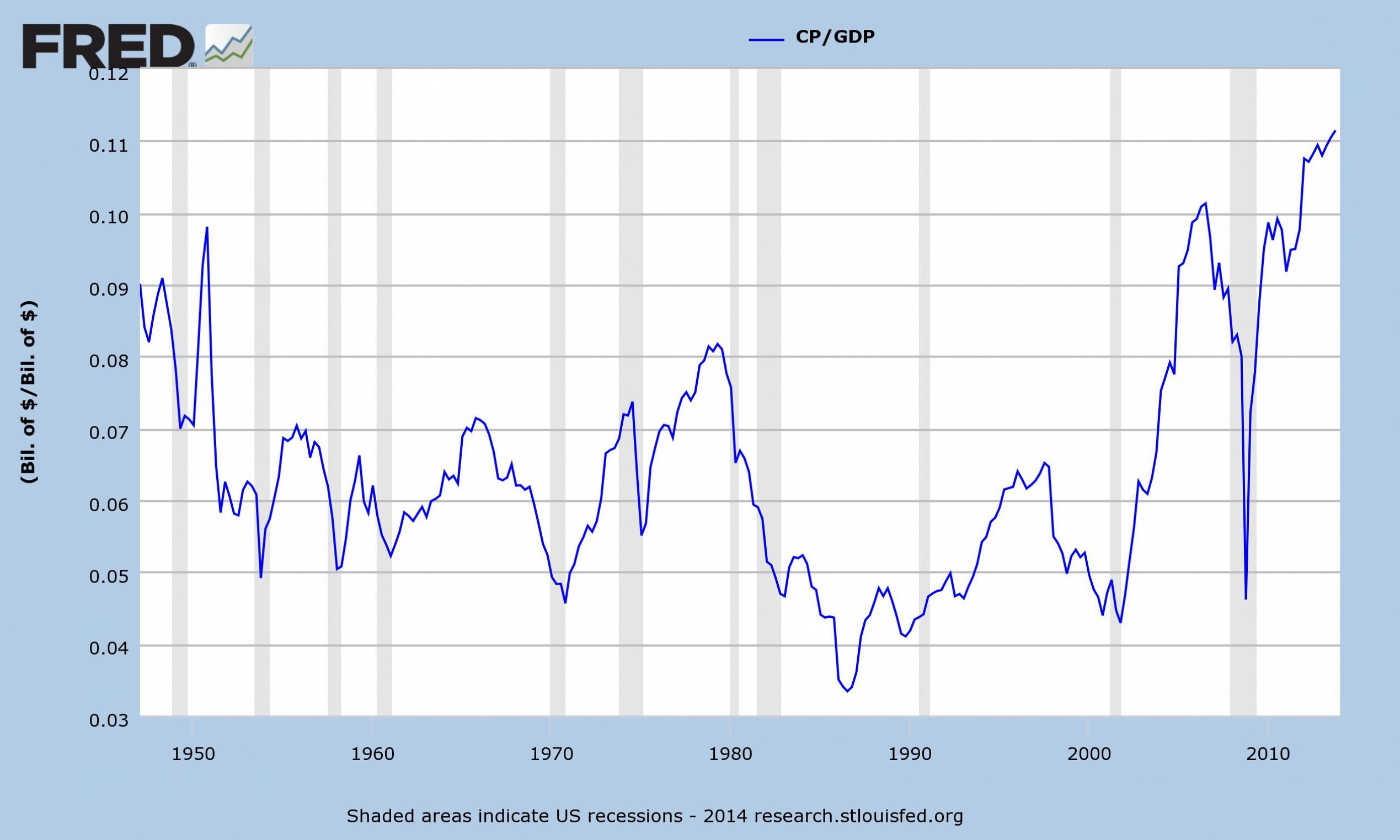

This chart is interesting because it shows a clear change in behavior at the start of the 1980’s. Although not in Piketty’s data set another pair of charts showing a similar change in behavior around the start of the 1980’s is the total debt to GDP ratio for the US and the fraction of national income taken by corporate profits.

An alternative story, describing the trends in these charts, could be constructed from a pair of emerging market shocks rather than a pair of World Wars.

Emerging Market Shock #1 - North American Agriculture

Throughout the 19th century European agriculture came under increasing competitive pressure from the emerging economies of North America. This pressure was stepped up around the middle of the 19th century with the abolition of the Corn Laws in England and later the end of the American Civil War in 1865. At around this time there was a major expansion of the railway system within North America and a dramatic improvement in the speed and reliability of sea freight, with the development of steam ships. Both the railways and the steam ships connected North American grain producers directly into the newly liberalized European export markets. This drove down grain prices and therefore European agricultural land values. Then in the 1880’s the invention of refrigerated shipping opened up the European markets to competition from foreign producers of meat and dairy produce.

As a result, European landowners were progressively priced out of the newly globalized food market. Farm rents and therefore land values fell, while on the other side of the coin, labor prices remained high due to increased demand for labor through emigration to North America and migration to industrial work.

These developments are well illustrated by the following passages:

“Free-trade policies, which had been fully introduced in the 1850’s and 1860’s had left British agriculture highly vulnerable to foreign competition, which proved to be the main factor in producing a long period of agricultural depression during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, as cheap cereals began to flow in from Canada, the USA, Australia and Argentina, while the invention of refrigerated shipping in the 1880’s brought livestock farmers too within the range of foreign competition. Agricultural prices, rents, and land values all fell sharply, undermining the economic basis of landed power…

…Following the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846, the living conditions of the labouring classes in England, roughly 70 percent of the whole population at that time, at last began to improve slowly at first but later at a quickening pace… The lowest paid of all the working classes throughout this period were the agricultural labourers… an index of their money wage levels in England and Wales moved from 72 in 1850 to 110 in 1901, a rise of 53 percent. In real terms, moreover, their wage rise had been even larger, because this increase in money wages had taken place against a background of generally falling prices…” Agriculture and Politics in England 1815-1939 J.R. Wordie

“The effects of depression on the three economic groups involved in farming were unequal…landlords fared worst with a decline of about 30 percent in their income from the land between 1880 and 1900…the group who fared best, mainly because of the huge decrease in their numbers from over 1.4 million in 1861 to around a million in 1911 , were farmworkers, whose average incomes rose by over 50 percent… by the 1890’s neither tenants nor landlords had sufficient capital left to adapt to new conditions…in East Anglia, Essex, Wiltshire, Oxfordshire, Berkshire or Kent rental values declined by over 36 percent between 1873 and 1911.” Agriculture in Depression 1870-1940, Richard Perren

Clearly the downward pressures on agricultural land, the main component of European capital, was in place long before World War I. Indeed the social disruption caused by the declining wealth of the landed aristocracy, coupled with the emergence of organised labor in the industrializing cities, makes it possible to paint a picture which reverses Piketty’s direction of causality between capital destruction and World War I. It could be argued that World War I was more a symptom of the social upheaval caused by the destruction of European agricultural capital rather than its cause. By 1914 the ruling elite had neither the wealth nor the incentive to preserve the status quo and avoid war.

The rise of North American agriculture could be considered as a land shock – suddenly the world had a dramatic increase in agricultural land and therefore a relative shortage of labor. The effect of this was to drive down the price of what the rich had – land – and drive up the price of what the poor had – labor – causing society to become more egalitarian.

Emerging Market Shock #2 - Chinese Manufacturing

The second emerging market shock began in the 1980’s and continues today with the rapid industrialization of the emerging market economies of Asia, Latin America and Eastern Europe but most especially China. Competitive pressures from cheap labor in these emerging economies held back wage growth in developed economies, especially in the Anglo Saxon economies which were most ideologically wedded free market competition.

In addition, the surge in low priced exports to the developed economies drove down inflation. The central banks of the developed economies responded to the lower inflationary pressures and weaker wage growth by attempting to artificially stimulate their domestic economic activity with lower interest rates. This policy, inadvertent or not, then lead directly to the asset price inflation which is behind the rise in the price of European housing and which is largely responsible for the increase in what Piketty classifies as European capital.

For global corporations this was the perfect scenario, they were able to maximize profits by borrowing money where it was cheapest – in effect from their domestic central banks – and combine those cheap funds with the cheap emerging market labor. Meanwhile their domestic customers were kept buoyant with a binge of debt fueled spending. Taken together, these factors conspired to drive up the profit to GDP ratio. At least some of what Piketty calls the super-managers managed to persuade their shareholders that this surging profitably was due to their own acumen rather than the twin tailwinds provided by central banks and cheap labor.

The rise of Chinese manufacturing could be considered as a labor shock – suddenly the world had a dramatic increase in labor and therefore a relative shortage of capital. The effect of this was to drive down the price of what the poor had – labor – and drive up the price of what the rich had – capital – causing society to become less egalitarian (at least when considered from the perspective of the Western worker).

This alternative narrative in no way diminishes the inequality problem that Piketty is highlighting but it does throw up an important challenge to his primary mathematical model. The destruction of European agricultural capital in the 19th century was not due to an exogenous World War but to an endogenous process of innovation. European agricultural capital was wiped out by connecting American farmers and cowboys to their European customers with the innovation of steam trains, steam ships and refrigeration.

Capitalism may be better viewed as an innovative, Darwinian, competitive struggle rather than a clockwork process of never ending accumulation. Winners – Apple’s iPhone – often create capital by destroying the capital of the losers – Nokia. This endogenous capital destruction is missing from Piketty’s mathematics but is well captured by Schumpeter’s creative-destruction.

Schumpeter’s model of creative destruction does not lend itself to simple mathematical modelling, none the less it has history on its side. The Austrian narrative approach to understanding economies may be imprecise but, at least until the mathematics catches up with reality, it should not be dismissed.